It was a simple idea: Combine the everyday music of Long Beach and nearby Compton with the ascendant sounds of funk, soul, and R&B, and shape it all into something that would sound right coming out of a radio anywhere in the United States. By the time they released The World Is a Ghetto in 1972, War had the levels dialed in perfectly.

The Long Beach party band had spent 1969 banging around Los Angeles County playing heavy R&B as the backing band for future NFL Hall of Famer Deacon Jones when producer Jerry Goldstein caught their live show. He thought they’d be a perfect match for English singer Eric Burdon, who was just beginning his solo career following the dissolution of the Animals. The interracial band—Burdon and harmonica player Lee Oskar were white, the rest of the band was Black—had a hit by mid-1970 with “Spill the Wine,” a talky pastoral funk song that set Burdon’s Kinks-indebted lyrics against a snapping rhythm. The singer would leave the group following 1970’s regrettably titled The Black Man’s Burdon, but the spirit of multicultural brotherhood—and the freedom from genre expectations it would provide—remained. Working closely with Goldstein, War became both a heavyweight live band and a sophisticated pop machine, slicker than Sly and the Family Stone and more down to earth than Funkadelic.

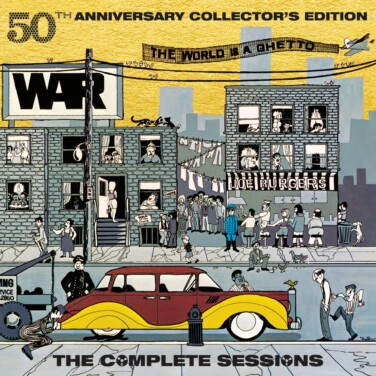

Five decades later, War are primarily remembered for 1975’s “Low Rider,” an all-time great song that’s been licensed so frequently and decontextualized so thoroughly it now feels like something of a novelty. Rhino’s new reissue of The World Is a Ghetto—the best-selling album of 1973, with a single that shipped a million copies—not only restores War’s reputation as some of the savviest and most omnivorous pop composers of the 1970s; its bonus disc of in-studio jams suggests they might have rivaled Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters as one of funk’s greatest groups of improvisers.

The World Is a Ghetto was originally intended to be a stage play that War percussionist Papa Dee Allen was developing about a character named Ghetto Man. One night, while the band was jamming in their Long Beach warehouse, he hit upon a revelation, as co-founder and keyboardist Lonnie Jordan recalls in the reissue’s liner notes. They’d been playing around in Malibu and Santa Monica, and had seen firsthand that wealth and privilege didn’t necessarily guarantee a great life. In their view, Ghetto Man wasn’t any different from the guy with the beachfront property who still struggled with addiction. And that changed how they saw the world: “The world is a ghetto.”